Indigenous design has evolved over untold millennia to bring forth anonymous innovations that have helped to preserve, satisfy, and advance the needs, wants, and dreams of human civilization. The Powhatan and Algonquin tribes, for instance, perfected companion growing and crop rotation cycles to offset famine, pests, and disease in the culmination of the Three Sisters, or the simultaneous growing of maize, beans, and squash.

Project Concept

Exploring indigenous design principles for modern climate resilience and sustainable infrastructure

Indigenous Design Heritage

Throughout the American Northwest, the Tillamook and Umpqua peoples of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians deployed permaculture infrastructure for animal enclosures, fish farms, and even domiciles. Willow trees have seemingly countless uses, because the plant can readily propagate and continue growing in almost any environment with designated carbon sequestration. Whereas barbed wire will rust and degrade over time, a living fence comprised of interlocking willow branch lattice structures will only get stronger with age.

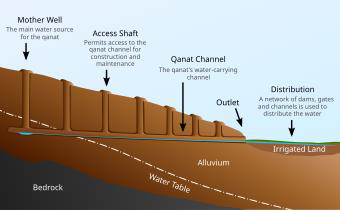

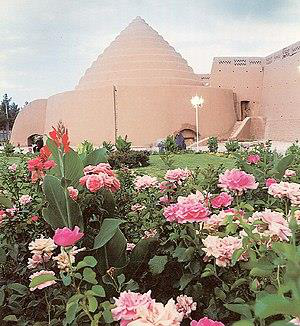

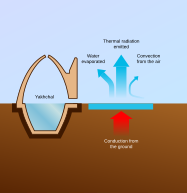

Ancient Persian Innovations

Inhabitants of ancient Persia devised ingenious badgir structures to cool buildings by directing wind currents to residential interiors and underground cistern-aqueducts or qanats that allowed people to store and transport water over great distances, and even enjoy ice in the harsh desert climes through cleverly integrated Yakhchāl structures.

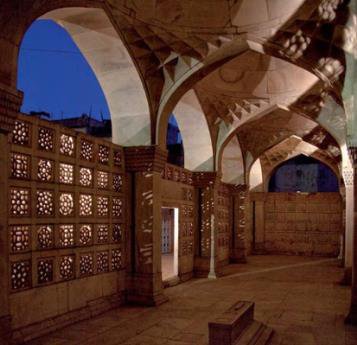

Mughal Empire & Water Systems

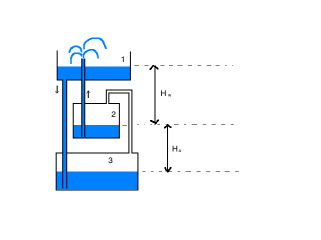

Engineers of the Mughal Empire developed analog air conditioning systems that produced evaporative cooling for temperature control by circulating water across the openings of terra cotta pipes. Water pumped ingeniously without electricity, through air pumps, pressure-differential systems, and modifications to Heron's Fountain promoted the intentional integration of rivers, rain basins, and lakes in urban infrastructure.

Indigenous Land Management

In her inspiring 2023 TED Talk, "3000-Year Old Solutions to Modern Problems," Dr. Lyla June, a Diné musician, scholar, and cultural historian, challenges the myth of the "primitive Indian" and shares groundbreaking insights from her doctoral research at the University of New Mexico. She reveals that Native peoples were not passive observers of nature, but rather active agents who shaped the land to produce prolific abundance for tens of thousands of years, becoming what ecologists call a "keystone species" upon which entire ecosystems depend.

Dr. Lyla June's 2023 TED Talk: "3000-Year Old Solutions to Modern Problems"

Dr. June presents four key Indigenous land management strategies that have proven effective for millennia:

1. Work with Nature: Rather than trying to control the earth, Indigenous farmers leverage pre-existing natural systems. In Southwest deserts, Native farmers place fields at the base of watersheds to catch monsoon rains and nutrients flowing from upland soils. This alluvial farming technique requires no outside fertilizers or irrigation and has allowed cultivation of the same plots for centuries without depleting the soil.

2. Intentional Habitat Expansion: Instead of confining plants and animals to farms and cages, Indigenous peoples create homes for them. For millennia, following the grass burning moon of lunar calendars, Native peoples used gentle fire to transform dead plant tissues into nutrient-dense ash, nourishing the soil and unlocking seeds of pyro-adapted grasses. This practice prevented trees from taking over grasslands and generated topsoils up to four feet deep. Contrary to popular belief, buffalo followed Native fire practices, not the other way around, allowing Indigenous peoples to anthropogenically expand buffalo habitat as far south as Louisiana and as far east as Pennsylvania.

3. De-Center Humans: Coastal Salish Nations of British Columbia enhance fish habitat by planting kelp forests where herring lay their eggs. By feeding the entire food web—from herring to bear, salmon, orca, eagles, and wolves—they ironically achieve greater food security for themselves. This non-human-centric approach demonstrates that by serving all life around them, Indigenous peoples feed the hand that feeds them.

4. Design for Perpetuity: Rather than planning for just the next fiscal quarter, Indigenous peoples design systems to last for generations. Fossil records from Kentucky show that Shawnee ancestors maintained a chestnut food forest for over 3,000 years through routine burning of the forest floor, which enriched the soil, helped it hold more water, and eliminated competing vegetation to boost tree immune systems.

Dr. June emphasizes that these continents were densely populated by Indigenous peoples, and their food systems successfully supported large populations. She argues that these systems may be even more efficient than industrial food systems because they protect and augment the very things that give us life, rather than extracting and destroying them.

However, Dr. June also makes a crucial point: it's not enough to simply mimic Native practices. We must also work to return lands to their original caretakers and heal the historical trauma of conquest, displacement, and cultural destruction. The Diné concept of "hózhó"—the joy of being part of the beauty of all creation—teaches that humanity has an ecological role and that Mother Earth needs us as her friend, ally, and partner, not as her dominator or profiteer.

Modern Applications

Scientific memory has tended to relegate the advances of indigenous peoples to the periphery. The exploitative regard for nature at the root of ever-consumptive Capitalism fails to accommodate an impartial review of values and practices that would improve material conditions for survival and mitigate detrimental externalities in the natural world.

In the context of international economic development, the Global South has been leading the charge on innovative practices to repurpose waste. Consider the devices and business methods of KAA AirInk in India, Plastic Brick Manufacturing by Nzambi Matee in Kenya, Clean Precious Metal Processing of eWaste by Mint Innovation in New Zealand, and Bioplastic production by Avani in Indonesia.

Green initiatives tend to be much more successful when they coincide with dominant cultural practices and values. Our status as consumers should always coincide with our shared prerogative to serve as stewards of nature.

Project Vision

This project envisions deploying indigenous design in the context of modern Richmond infrastructure. Following the model of An Liu's Helper Initiative, the central aim of this project would be to plan and prepare proposals for community beautification, city climate resilience grants, and data-driven responses to improve and ameliorate environmental impact statements, upcycling waste streams, and forging partnerships with strategic firms, organizations, and government representatives to advance these manifold goals.

Although still in the planning stages, the hope is that continued research into Native Earthways will advance climate resilience and sustainability initiatives in the greater Richmond area, promoting improved understandings of environmental stewardship and more conscientious institutional and individual behavior with respect to resource consumption, urban infrastructure, and the utilization of carbon-intensive energy needs.